Introduction to musical pitch

Frequency: a physical attribute of a sound, which can be measured in cycles per second, or Hertz (we will look at cycles and pitch measurement in detail soon)

Pitch: "that property of a sound that enables it to be ordered on a scale going from low to high" (Acoustical Society of Amerca)

Frequency is an objective property of sounds in the physical world, pitch is a perceived property of sounds.

"If a tree falls and no one hears it, does it make a sound?"

That depends on whether we are talking about physical sound, or perceived sound!

While it is not correct to equate pitch and frequency, it is true that the main physical correlate of pitch is frequency.

There is much more to the perception of musical pitch than simply saying that one sound is higher or lower than another. Some sounds, or notes, have a special relationship to one another, beyond just being higher or lower to some degree. And this organization of pitch is at least somewhat culturally specific, and therefore learned. We'll look at the basics of scales in mainstream Western music (shared by classical and popular music), and then look a scale in a very different musical tradition, that of Indonesian Gamelan music.

Basics of Western scales

The octave

We have the impression that some notes are in some sense the "same", even though their pitch is different. These are the notes that form an octave. The term "octave" is specific to the Western tradition, but the notion and sensation of identical sounds of different pitches may well be universal.

An octave generally corresponds to a doubling of frequency. So a note at 440 Hz ("A" in standard Western tuning), will form an octave with notes at 880 Hz and 220 Hz (two more As).

It seems that all musical traditions recognize in some way the equivalency of notes an octave apart, even if they don't have a term for it. The universality of the octave is likely related to physical properties of the auditory system. Infants as young as three months respond to octaves differently from other intervals (Demany & Armand 1984), as do Rhesus monkeys (Wright et al. 2000).

The piano keyboard is organized into octaves. You can see that the white notes with a given label (e.g. "C") are found in a consistent position with respect to the groups of black keys (C is immediately to the left of the group of two black keys).

Here is an octave interval in C being played, compared with the interval from C to B (a major seventh). Hopefully, in the first case, but not the second, it will sound to you like the same note is being played at different pitches. (Geek tech note: this is the "Wurlie Jazz" preset of Arturia's Analog Lab synthesizer).

Semi-tones, whole tones and scales

In Western music, octaves are divided into 12 equally (logarithmically) spaced intervals, called semi-tones. On the keyboard, a sequence of semi-tone intervals is produced by playing a sequence of keys, including both the white and the black keys. (A chromatic scale).

On a guitar, the frets are placed at semi-tone intervals. The guitar string is tuned to E, so this time it's an octave from E to E, rather than the C to C in the keyboard video.

A scale is a division of the octave into a set of notes used to construct melodies. Chromatic scales using all of the semi-tones are uncommon. Instead, in Western music a scale usually consists of a choice of seven of the twelve notes in an octave (eight counting the octave itself). On a piano keyboard, a major scale can be produced by starting at C, and playing only the white keys until you get to the next C. (Sometimes termed a diatonic scale).

You'll notice that in terms of semi-tones, the spacing between the notes of the scale is not consistent: the 3rd and the 4th notes (E and F) and the 7th and 8th (B and C) are only a semi-tone apart, whereas the others are two semi-tones, or a whole tone apart. On the keyboard, the notes in the C major scale separated by a whole tone have a black key between them, while those separated by a semi-tone are right beside each other. The unequal spacing of a major scale can be clearly seen when we play one going up a single string on a guitar. Since the guitar string played in the video is tuned to E this is an E major scale. (Note: Scales are not usually played with one finger on one string!)

In a minor scale, the third note is a semi-tone lower. So, on the piano keyboard, instead of playing the white key for the third note of the C scale, we play the black one to its left. This note is called E flat. Now it's the 2nd and 3rd notes, rather than 3rd and 4th, that are right beside each other in terms of semi-tones. In the video, you'll first hear a C minor scale, and then pairs of arpeggios (a repeated sequence of notes), the first pair minor, and the second major. (This is actually an unusual C minor scale, since it usually also contains at least a flatted 7th, and perhaps flatted 6th too).

Western popular music also often uses a flatted seventh note, or minor seventh. In our C scale, that will be a B-flat. This puts the 6th and 7th notes close together, rather than the 7th and 8th. If we play a scale with both a flatted third and flatted seventh, it will sound typical of blues music (more on that below). In the video, the C minor seventh scale is followed by contrasting minor seventh and major arpeggios.

The unequal spacing of the notes in a scale forms the basis for an interesting demonstration of the effects of our knowledge of musical pitch on perception. Shepard and Jordan (1984: abstract):

Judgments of relations between tones in a sequence derived from the major diatonic scale (do, re, mi, . . .) by systematic distortions (either equalization or stretching of intervals) reveal that Western listeners interpret the tones relative to that musical scale even when they try to judge the purely physical relations between the tones.

Patel (2008: 22):

The interesting result was that participants judged the 3rd and the 7th intervals to be larger than the others. These are precisely the intervals that are small (1 semitone) in a Western musical scale, suggesting that listeners had assimilated a novel scale to a set of internal sound categories. It is especially notable that these learned internal interval standards were applied automatically, even when instructions did not encourage musical listening.

Balinese gamelan music and pentatonic scales

The Indonesian gamelan (orchestra) is made up of several different kinds of instrument. We'll be looking at a Balinese gamelan; Javanese gamelans are closely related, but differ in some respects. The gangsa family of instruments have bronze keys that are suspended over bamboo resonators. They are struck by a wooden hammer held in the right hand, and the left hand is used to damp the key (stop it from vibrating) when the next key is struck. Balinese gamelan music is noted for being particularly fast, and this co-ordinated striking and damping requires considerable technical proficiency. You can see that in this video (Click the image to view).

There are many differences between gamelan music and Western music. Gamelan music does not involve chords, or harmony; it is purely melodic. The rhythmic structures, and overall song structures are also very different from Western music. The instruments in a gamelan are often tuned slightly differently from one another to produce beats, and a shimmer. This is of course usually avoided in Western music (though "detuning" is sometimes used in synthesizers to "thicken" a sound).

The scales used in Gamelan music are quite different from Western music. The Balinese Gamelan scale that we heard in the video and in the class is a pentatonic scale: instead of seven notes as in the Western scales we discussed above, there are five. And as we discovered in class, the spacing is quite different from a Western scale (even from Western pentatonic scales). The webpage linked here has an excellent discussion of the tuning of Balinese gamelans. It concludes by saying that we can approximate the Balinese gamelan scale by playing the following notes on a keyboard:

C, C#, D#, G and G#

The # symbol means "sharp" - this is the black key to the right of the indicated note.

In terms of intervals, the Gamelan scale looks like this (where 1 = a semi-tone interval):

1-2-4-1-4

One common pentatonic scale in Western music is the minor pentatonic scale, which uses the root note (e.g. C in C), flatted third, the fourth, the fifth, and the flatted seventh. As mentioned above, moving from a white key to the black key to the left is the "flat"; the flat symbol is ♭. This is a simple blues scale, and is often the first scale learned by guitar players (it's particularly easy to play on a guitar, and works well on standard blues/rock chord progressions).

In a C scale, the minor pentatonic is:

C, E♭, F, G, and B♭

The intervals are the following:

3-2-2-3-2

Notice that the Gamelan pentatonic scale uses much more uneven intervals than the Western one. Notice as well that both scales have one interval / note in common: the G, which in Western music theory is a fifth with respect to C (the fifth note in the major scale). As we will discuss further, the fifth is a special interval, and is present in most musical systems.

Here is a video that compares the Balinese and Western pentatonic scales in C on a keyboard. Each one is played twice.

Here's the Western pentatonic scale on a guitar in A, followed by a little "noodling" using that scale. (Noodling = aimless improvisation)

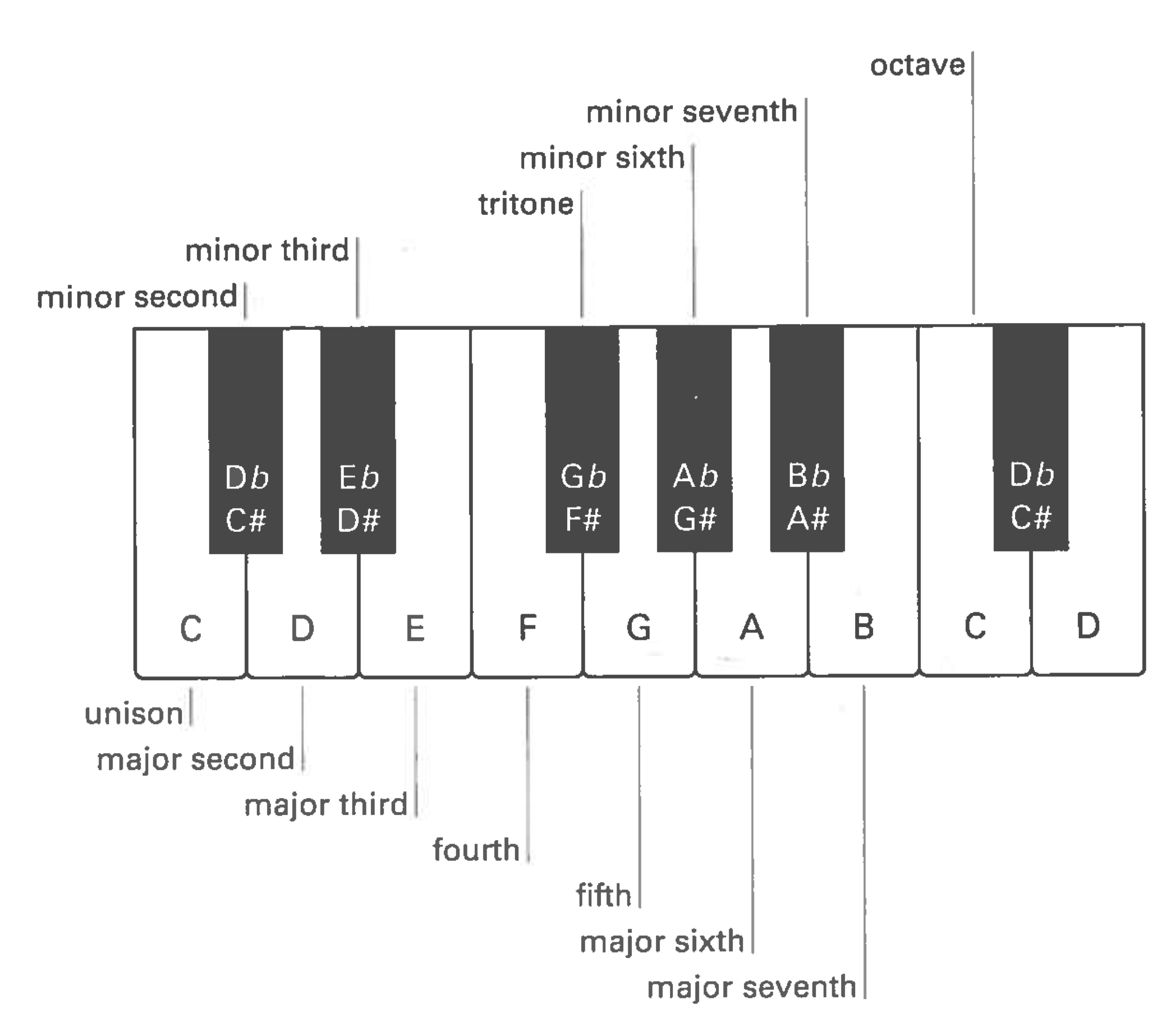

The diagram below from Schnupp et al. (2012) shows the names of all of the notes, including sharps and flats, and names for all of the intervals in C.